On December 2nd, 1938, 200 young people descended a ship’s gangplank in the Essex port of Harwich. They came from Germany without their parents, siblings, family, friends; they came alone.

These 200 were the vanguard of one of the largest acts of rescue in the Holocaust era. They were Jewish children from orphanages and homes that had been torched, battered or smashed by Nazi thugs on November 9th and 10th, 1938, – the so called ‘Kristallnacht’, the Night of Broken Glass.

The children had witnessed SS and Hitler Youth beating up their parents, wrecking their homes and businesses, arresting men and carting them off to be brutalised in concentration camps.

It was after this terrible night that parents in Germany decided to send their children to safety.

The children had no one in Britain to look after them; homes and support had to be found. Their arrival was entirely in the hands of volunteers as the British Government took no part in their rescue from persecution. Enter an army of British helpers among whom were Rotarians.

Listen to this article

The children who arrived on that sunny December day had come on a train that left Germany the day before, travelled across the border into the Netherlands, on to the Hook of Holland and the night ferry to Harwich.

This was the preferred route of most of the 10,000 children who came to Britain on the ‘Kindertransport’.

The last such transport arrived in Harwich on September 2nd, 1939, one day before war was declared.

Then, all borders were closed, the fate sealed for the Jewish children and their families, left at the mercy of the murderous Nazi state.

The nerve centre of this massive rescue operation was at Bloomsbury House in central London. Here committees were hurriedly set up by Jewish, Quaker, Church of England, Methodist and other relief bodies.

The Rotarians were an astoundingly active organisation who rolled up their sleeves to provide assistance to these benighted children.

Among these were Alfred Roberts, whose daughter Margaret – later Thatcher – became Prime Minister. Another was Frederick Attenborough, father of the naturalist David.

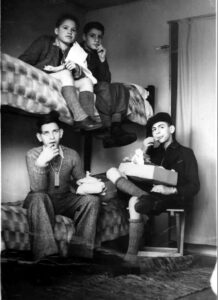

Jewish refugee children from Germany in a camp in Great Britain. © Wiener Holocaust Library.

In each case they not only drew on their Rotarian networks for support but also went the extra mile in providing a home for German Jewish refugee children. The task was enormous: to find homes for the 10,000 youngsters.

Though formal research on the role of the Rotarian in the Kindertransport rescue has not been done, clues to the help given can be found in newspaper archives and sometimes in the rare existing records of the refugee committees.

The Worthing Herald for January 6th, 1939 reported that Worthing Rotary Club had decided to ‘adopt’ two refugee children from Germany and an adult from Czechoslovakia who was forced to flee his country.

In practice, this meant Rotarians provided financial support for the children (a necessary condition of the visa waiver scheme) and foster homes in Worthing.

The club’s President, Mr Linwood, hoped that this example would be copied by other clubs who were part of ‘Rotary International of the British Isles’.

It was, he added, a way for Rotarians in Worthing to truly live up to the ideals of the club.

The way the Rotarians got together to help these children is exemplified in the story of Edith Mühlbauer.

She was a Jewish youngster from Nazi-controlled Vienna, aged around 16 or 17, who on January 21st, 1939, received a letter that would save her life. It was from her penpal Margaret Roberts, the future Prime Minister.

After the pogroms in November 1938, Edith wrote to Muriel Roberts in Grantham desperately seeking help to get out of Austria. Muriel, sister of Margaret, told Edith that her father, a local grocer, was keen to help.

The range of support for these children by Rotarians extended from fundraising appeals, talks to raise awareness of their plight and the provision of safe homes for the refugees.”

An active member of the Grantham Rotary Club, Albert Roberts read out the appeal from Edith and asked for help. The club members decided to bring her over to England and supported her with a guinea a week pocket money.

Too old for the Kindertransport scheme, the Grantham Rotary Club helped get Edith a visa to travel to England. About that life-saving visa, Edith wrote to the Roberts, ‘I thank you very much for sending it. I will never in my whole life forget you.’

By April 1939, Edith had arrived in Grantham with two presents: handbags for Muriel and 13-year-old Margaret.

Their father, also a local preacher, ignored some local voices expressing anti-semitic views, and opened his home to Edith. It was not an entirely happy affair as Edith found the Roberts family kind but rather cold, so she was moved to another Rotarian family in the town.

Later in life, Edith looked back on that letter from Muriel Roberts: “If Muriel had said, ‘I am sorry, my father says no’, I would have stayed in Vienna and they would have killed me.”

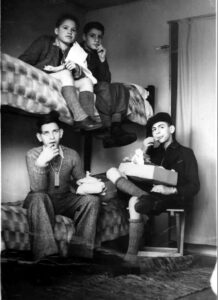

The children who arrived in Harwich had come on a train that left Germany the day before. © Wiener Holocaust Library.

In a similar vein, Frederick Attenborough, President of the Leicester Rotary Club, also won support for looking after Jewish refugee children.

He and his wife took in two German Jewish sisters who became part of the Attenborough family for the rest of their lives.

The range of support for these children by Rotarians extended from fundraising appeals, talks to raise awareness of their plight and the provision of safe homes for the refugees.

One such talk was given by the Rev W.W. Simpson to Bristol Rotarians on May 15th, 1939.

The Western Daily Press reported that Simpson, later a co-founder of the Council of Christians and Jews, said: “No movement was better qualified than Rotary because of its ideals and its constitution – to interest itself in the refugee problem.”

Though the scale of the Rotarian response to Hitler’s persecution of its tiny Jewish minority (less than 1% of the German population), is not yet known, there is no doubt that the movement played a significant role in the help of refugees and the Kindertransport children in particular.

Mike Levy is the author of the book ‘Get the Children Out! Unsung Heroes of the Kindertransport’. He is currently researching British families who took in Kindertransport refugees. If your family, or someone you know, hosted a Jewish refugee from 1938, contact Mike at mike.levy82@gmail.com.